The Midi Kit is the API that implements support for generating, processing, and playing music in MIDI format. More...

Files | |

| file | Midi2Defs.h |

| Some definitions to define raw MIDI events. | |

| file | MidiConsumer.h |

| Defines consumer classes for the MIDI Kit. | |

| file | MidiEndpoint.h |

| Defines the Baseclass of all MIDI consumers and producers. | |

| file | MidiProducer.h |

| Defines producer classes for the MIDI Kit. | |

| file | MidiRoster.h |

| Defines the heart of the MIDI Kit: the MIDI Roster. | |

Classes | |

| class | BMidiConsumer |

| Receives MIDI events from a producer. More... | |

| class | BMidiEndpoint |

| Base class for all MIDI endpoints. More... | |

| class | BMidiLocalConsumer |

| A consumer endpoint that is created by your own application. More... | |

| class | BMidiLocalProducer |

| A producer endpoint that is created by your own application. More... | |

| class | BMidiProducer |

| Streams MIDI events to connected consumers. More... | |

| class | BMidiRoster |

| Interface to the system-wide Midi Roster. More... | |

Detailed Description

The Midi Kit is the API that implements support for generating, processing, and playing music in MIDI format.

MIDI, which stands for 'Musical Instrument Digital Interface', is a well-established standard for representing and communicating musical data. This document serves as an overview. If you would like to see all the components, please look at the list with classes .

A Tale of Two MIDI Kits

BeOS comes with two different, but compatible Midi Kits. This documentation focuses on the "new" Midi Kit, or midi2 as we like to call it, that was introduced with BeOS R5. The old kit, which we'll refer to as midi1, is more complete than the new kit, but less powerful.

Both kits let you create so-called MIDI endpoints, but the endpoints from midi1 cannot be shared between different applications. The midi2 kit solves that problem, but unlike midi1 it does not include a General MIDI softsynth, nor does it have a facility for reading and playing Standard MIDI Files. Don't worry: both kits are compatible and you can mix-and-match them in your applications.

The main differences between the two kits:

- Instead of one BMidi object that both produces and consumes events, we have BMidiProducer and BMidiConsumer.

- Applications are capable of sharing MIDI producers and consumers with other applications via the centralized Midi Roster.

- Physical MIDI ports are now sharable without apps "stealing" events from each other.

- Applications can now send/receive raw MIDI byte streams (useful if an application has its own MIDI parser/engine).

- Channels are numbered 0–15, not 1–16

- Timing is now specified in microseconds rather than milliseconds.

Midi Kit Concepts

A brief overview of the elements that comprise the Midi Kit:

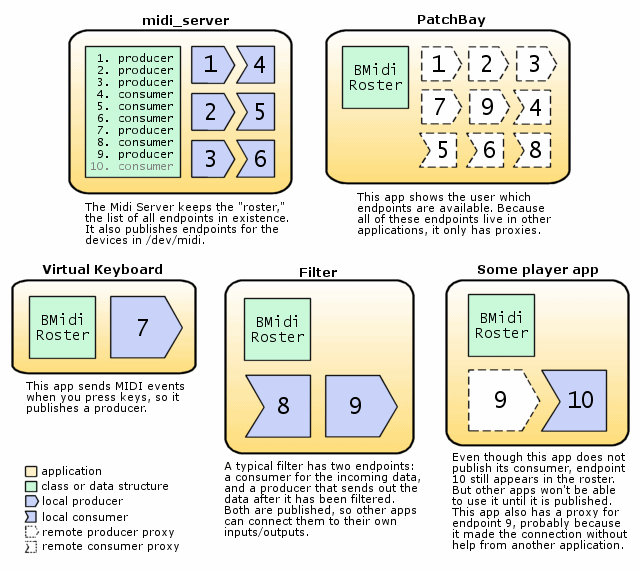

- Endpoints. This is what the Midi Kit is all about: sending MIDI messages between endpoints. An endpoint is like a MIDI In or MIDI Out socket on your equipment; it either receives information or it sends information. Endpoints that send MIDI events are called producers; the endpoints that receive those events are called consumers. An endpoint that is created by your own application is called local; endpoints from other applications are remote. You can access remote endpoints using proxies.

- Filters. A filter is an object that has a consumer and a producer endpoint. It reads incoming events from its consumer, performs some operation, and tells its producer to send out the results. In its current form, the Midi Kit doesn't provide any special facilities for writing filters.

- Midi Roster. The roster is the list of all published producers and consumers. By publishing an endpoint, you allow other applications to talk to it. You are not required to publish your endpoints, in which case only your own application can use them.

- Midi Server. The Midi Server does the behind-the-scenes work. It manages the roster, it connects endpoints, it makes sure that endpoints can communicate, and so on. The Midi Server is started automatically when BeOS boots, and you never have to deal with it directly. Just remember that it runs the show.

- libmidi. The BMidi* classes live inside two shared libraries: libmidi.so and libmidi2.so. If you write an application that uses old Midi Kit, you must link it to libmidi.so. Applications that use the new Midi Kit must link to libmidi2.so. If you want to mix-and-match both kits, you should also link to both libraries.

Here is a pretty picture:

Midi Kit != Media Kit

Be chose not to integrate the Midi Kit into the Media Kit as another media type, mainly because MIDI doesn't require any of the format negotiation that other media types need. Although the two kits look similar – both have a "roster" for finding or registering "consumers" and "producers" – there are some very important differences.

The first and most important point to note is that BMidiConsumer and BMidiProducer in the Midi Kit are NOT directly analogous to BBufferConsumer and BBufferProducer in the Media Kit! In the Media Kit, consumers and producers are the data consuming and producing properties of a media node. A filter in the Media Kit, therefore, inherits from both BBufferConsumer and BBufferProducer, and implements their virtual member functions to do its work.

In the Midi Kit, consumers and producers act as endpoints of MIDI data connections, much as media_source and media_destination do in the Media Kit. Thus, a MIDI filter does not derive from BMidiConsumer and BMidiProducer; instead, it contains BMidiConsumer and BMidiProducer objects for each of its distinct endpoints that connect to other MIDI objects. The Midi Kit does not allow the use of multiple virtual inheritance, so you can't create an object that's both a BMidiConsumer and a BMidiProducer.

This also contrasts with the old Midi Kit's conception of a BMidi object, which stood for an object that both received and sent MIDI data. In the new Midi Kit, the endpoints of MIDI connections are all that matters. What lies between the endpoints, i.e. how a MIDI filter is actually structured, is entirely at your discretion.

Also, rather than use token structs like media_node to make connections via the MediaRoster, the new kit makes the connections directly via the BMidiProducer object.

Remote vs. Local Objects

The Midi Kit makes a distinction between remote and local MIDI objects. You can only create local MIDI endpoints, which derive from either BMidiLocalConsumer or BMidiLocalProducer. Remote endpoints are endpoints that live in other applications, and you access them through BMidiRoster.

BMidiRoster only gives you access to BMidiEndpoints, BMidiConsumers, and BMidiProducers. When you want to talk to remote MIDI objects, you do so through the proxy objects that BMidiRoster provides. Unlike BMidiLocalConsumer and BMidiLocalProducer, these classes do not provide a lot of functions. That is intentional. In order to hide the details of communication with MIDI endpoints in other applications, the Midi Kit must hide the details of how a particular endpoint is implemented.

So what can you do with remote objects? Only what BMidiConsumer, BMidiProducer, and BMidiEndpoint will let you do. You can connect objects, get the properties of these objects – and that's about it.

Creating and Destroying Objects

The constructors and destructors of most midi2 classes are private, which means that you cannot directly create them using the C++ new operator, on the stack, or as globals. Nor can you delete them. Instead, these objects are obtained through BMidiRoster. The only two exceptions to this rule are BMidiLocalConsumer and BMidiLocalProducer. These two objects may be directly created and subclassed by developers.

Reference Counting

Each MIDI endpoint has a reference count associated with it, so that the Midi Roster can do proper bookkeeping. When you construct a BMidiLocalProducer or BMidiLocalConsumer endpoint, it starts with a reference count of 1. In addition, BMidiRoster increments the reference count of any object it hands to you as a result of NextEndpoint() or FindEndpoint() . Once the count hits 0, the endpoint will be deleted.

This means that, to delete an endpoint, you don't call the delete operator directly; instead, you call Release() . To balance this call, there's also an Acquire() , in case you have two disparate parts of your application working with the endpoint, and you don't want to have to keep track of who needs to Release() the endpoint.

When you're done with any endpoint object, you must Release() it. This is true for both local and remote objects. Repeat after me: Release() when you're done.

MIDI Events

To make some actual music, you need to Connect() your consumers to your producers. Then you tell the producer to "spray" MIDI events to all the connected consumers. The consumers are notified of these incoming events through a set of hook functions.

The Midi Kit already provides a set of commonly used spray functions, such as SprayNoteOn() , SprayControlChange() , and so on. These correspond one-to-one with the message types from the MIDI spec. You don't need to be a MIDI expert to use the kit, but of course some knowledge of the protocol helps. If you are really hardcore, you can also use the SprayData() to send raw MIDI events to the consumers.

At the consumer side, a dedicated thread invokes a hook function for every incoming MIDI event. For every spray function, there is a corresponding hook function, e.g. NoteOn() and ControlChange() . The hardcore MIDI fanatics among you will be pleased to know that you can also tap into the Data() hook and get your hands dirty with the raw MIDI data.

Time

The spray and hook functions accept a bigtime_t parameter named "time". This indicates when the MIDI event should be performed. The time is given in microseconds since the computer booted. To get the current tick measurement, you call the system_time() function from the Kernel Kit.

If you override a hook function in one of your consumer objects, it should look at the time argument, wait until the designated time, and then perform its action. The preferred method is to use the Kernel Kit's snooze_until() function, which sends the consumer thread to sleep until the requested time has come. (Or, if the time has already passed, returns immediately.)

Like this:

If you want your producers to run in real time, i.e. they produce MIDI data that needs to be performed immediately, you should pass time 0 to the spray functions (which also happens to be the default value). Since time 0 has already passed, snooze_until() returns immediately, and the consumer will process the events as soon as they are received.

To schedule MIDI events for a performance time that lies somewhere in the future, the producer must take into account the consumer's latency. Producers should attempt to get notes to the consumer by or before (scheduled_performance_time - latency). The time argument is still the scheduled performance time, so if your consumer has latency, it should snooze like this before it starts to perform the events:

Note that a typical producer sends out its events as soon as it can; unlike a consumer, it does not have to snooze.

Other Timing Issues

Each consumer object uses a Kernel Kit port to receive MIDI events from connected producers. The queue for this port is only 1 message deep. This means that if the consumer thread is asleep in a snooze_until(), it will not read its port. Consequently, any producer that tries to write a new event to this port will block until the consumer thread is ready to receive a new message. This is intentional, because it prevents producers from generating and queueing up thousands of events.

This mechanism, while simple, puts on the producer the responsibility for sorting the events in time. Suppose your producer sends three Note On events, the first on t + 0, the second on t + 4, and the third on t + 2. This last event won't be received until after t + 4, so it will be two ticks too late. If this sort of thing can happen with your producer, you should somehow sort the events before you spray them. Of course, if you have two or more producers connected to the same consumer, it is nearly impossible to sort this all out (pardon the pun). So it is not wise to send the same kinds of events from more than one producer to one consumer at the same time.

The article Introduction to MIDI, Part 2 in OpenBeOS Newsletter 36 describes this problem in more detail, and provides a solution. Go read it now!

Writing a Filter

A typical filter contains a consumer and a producer endpoint. It receives events from the consumer, processes them, and sends them out again using the producer. The consumer endpoint is a subclass of BMidiLocalConsumer, whereas the producer is simply a BMidiLocalProducer, not a subclass. This is a common configuration, because consumers work by overriding the event hooks to do work when MIDI data arrives. Producers work by sending an event when you call their member functions. You should hardly ever need to derive from BMidiLocalProducer (unless you need to know when the producer gets connected or disconnected, perhaps), but you'll always have to override one or more of BMidiLocalConsumer's member functions to do something useful with incoming data.

Filters should ignore the time argument from the spray and hook functions, and simply pass it on unchanged. Objects that only filter data should process the event as quickly as possible and be done with it. Do not snooze_until() in the consumer endpoint of a filter!

API Differences

As far as the end user is concerned, the Haiku Midi Kit is mostly the same as the BeOS R5 kits, although there are a few small differences in the API (mostly bug fixes):

- BMidiEndpoint::IsPersistent() always returns false.

- The B_MIDI_CHANGE_LATENCY notification is now properly sent. The Be kit incorrectly set be:op to B_MIDI_CHANGED_NAME, even though the rest of the message was properly structured.

- If creating a local endpoint fails, you can still Release() the object without crashing into the debugger.

See also

More about the Midi Kit:

- Midi2Defs.h

- Be Newsletter Volume 3, Issue 47 - Motor Mix sample code

- Be Newsletter Volume 4, Issue 3 - Overview of the new kit

- Newsletter 33, Introduction to MIDI, Part 1

- Newsletter 36, Introduction to MIDI, Part 2

- Sample code and other goodies at the Haiku Midi Kit team page

Information about MIDI in general:

- MIDI Manufacturers Association

- MIDI Tutorials

- MIDI Specification

- Standard MIDI File Format

- Jim Menard's MIDI Reference

Please have a look at the introduction for a more comprehensive overview on how everything ties together.